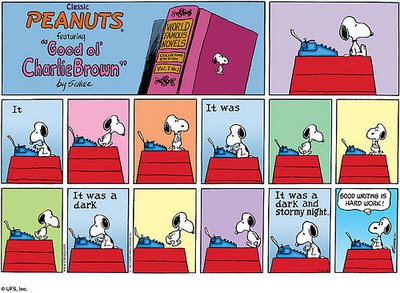

Edward Bulwer-Lytton's greatest impact on literature may be the opening line of his novel Paul Clifford. It was picked up by no less a character than Snoopy the dog in Charles Shultz's great cartoon series Peanuts.

It was used as the opening line in the Newberry Award winning novel A Wrinkle in Time.

It was a dark and stormy night.

In her attic bedroom Margaret Murry, wrapped in an old patchwork quilt, sat on the foot of her bed and watched the trees tossing in the frenzied lashing of the wind. Behind the trees clouds scudded frantically across the sky. Every few moments the moon ripped through them, creating wraithlike shadows that raced along the ground.

The house shook.

Wrapped in her quilt, Meg shook.Wikipedia informs me that Joni Mitchell used the line to start her song "The Crazy Cries of Love."

You'd think that the author of that line would be well-regarded, especially since he also originated other well-known phrases, from "the great unwashed" to "The pen is mightier than the sword." However, the Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest, which has given me much pleasure over the years, celebrates his reputation as a writer of terrible prose.

Still, he's famous. In particular, I have often read the title of his novel The Coming Race in histories of the science fiction genre. In it, I've heard, he tells about a superior race of people whose power is based on the control of a fundamental life force called vril, a term that lives on in the form of the beef drink Bovril.

So, eventually, I had to read The Coming Race to see what it is like. I found a free copy on Feedbooks that is based on the free version from Project Gutenberg.

Overall, I can say that its setting is a staider version of the underground worlds described by Jules Verne (in Journey to the Centre of the Earth) and Edgar Rice Burroughs' (in At the Earth's Core and the other Pellucidar novels). Like them, The Coming Race describes a system of hollows underground that contain reptilian species that either perished from the upper world or never lived there at all and a civilization that lacks knowledge of the upper world. Granted, the underground hollow in Burroughs' novel is expanded to the point that the world we know is only a shell around the interior world, and its dominant civilization belongs to intelligent reptiles, but the basic similarities remain. I wonder if Verne's novel, published seven years before The Coming Race, was one of its inspirations. The Burroughs novel came later, in 1914.

In theme and even plot, The Coming Race reminds me a bit of H.G. Wells' Men Like Gods (1923). Both books show a physically and morally superior commonwealth through the eyes of contemporary human beings who do not (on the whole) like it very much. On the other hand, we are given very little reason to respect the people who represent our points of view. The situation is ripe for satire. Like Wells, Bulwer-Lytton did not neglect the the opportunity.

For example, Chapter 9 tells that the Vril-ya people have legends about entering their caverns as they fled a flood in the upper world. (Is Bulwer-Lytton hinting that they are Atlanteans, or refugees of Noah's flood?) Although Bulwer-Lytton makes it clear that this origin story is the truth, most of the Vril-ya themselves no longer believe it. Coincidentally, in 1872, one year after the publication of The Coming Race, the Assyriologist George Smith published the Mesopotamian Flood Myth contained in the Epic of Gilgamesh. That confirmed the reality of the Biblical Flood in the minds of many people although many others, similar in spirit to the Vril-ya, disbelieved its literal truth.

Another example of his satire is directed at Darwin's Theory of Evolution as it applies to mankind. The Theory of Evolution was new and controversial at the time: Although Darwin's The Origin of Species was published in 1859, his Descent of Man came out in 1871, the same year as The Coming Race; T.H. Huxley's Man's Place in Nature was published eight years earlier. The Vril-ya, says Bulwer-Lytton (Chapter 16), once had much argument over the origin of man, but had settled that topic by agreeing that they were descended from "the Great Tadpole." Among the evidence they adduce for this are the similarities in appearance of humans and frogs, the presence of an atrophied swimming bladder, and ancient paintings of sages who resemble frogs more than modern Vril-ya do.

Based on this book, I assume that Bulwer-Lytton was no fan of Darwin's evolutionary theory. Instead, he seems to favour Lamarckism, saying

We are all formed by custom--even the difference of our race from the savage is but the transmitted continuance of custom, which becomes, through hereditary descent, part and parcel of our nature.Indeed, the Vril-ya are described as having a physical difference from other people, one that allows them to generate and control the vril better than any other race of humans. This is explained as the result of generations of practice, rather than selective breeding.

Some of the humour is close to farce. For example, not one but two women are romantically interested in the tiny, timid barbarian who narrates the book. One woman is the highest-ranked scholar in the community and the other, the daughter of its political leader. If he had been bolder then he would be part of one of the oddest couples imaginable. Then, shortly after, he would be executed before he could pollute the Vril-ya's gene pool.

In addition to satire and farce, some of the book's humour is purely word play. For example, narrator insists on using the Vril-ya's word for a woman, "gy," to refer to any of the the tall, physically powerful, beautiful women. Since the narrator is too intimidated by these women to respond to their romantic advances, the fact that he calls them "guys" is halfway between ironic and revealing. Another example of the author's word play is the word for democracy, Koom-Posh, which means "That nonsense (bosh) about the masses."

Outcrops of dry humour also occur in lumbering sentences such as

In this resolve I obeyed the ordinary instinct of civilized and moral man, who, erring though he be, still prefers the right course in those cases where it is obviously against his inclinations, his interests, and his safety to elect the wrong one.Unfortunately, the book is slow to get going. Not until Chapter 4 do we meet a Vril-ya. (At which sight, our fearless leader faints). Not until Chapter 6 is he able to speak with one. Chapter 10 has a long description of the Vril-ya's working life (what little of it exists) and marriage customs. Chapter 11, the lighting arrangements of the underground world. Chapter 12, the language of the Vril-ya, which is apparently Indo-European. Chapters 13 and 14 are on the religious beliefs.

The Coming Race is far from the best book of its type that I've read. It is even far from the best book of that type from that era, as H. Rider Haggard's "Lost Civilization" stories such as King Solomon's Mines and She were published only a few years after Bulwer-Lytton's book. On the other hand, his book has never fallen into oblivion. In fact, just yesterday I discovered that the sequel for the satirical movie Iron Sky is to be called Iron Sky: The Coming Race. Like Bulwer-Lytton's book, it features an unknown civilization underground, co-existing with giant reptiles (well, dinosaurs), and posing an existential threat to us dwellers on the world's surface. The movie's title and content are a pretty compliment to a Victorian writer who is often listed as one of the world's worst writers.